Set marketing strategy and adjust the marketing plan to drive the business development plan at any phase of the business cycle.

Adjusting marketing strategy and the marketing plan to maximise opportunity in a downturn is the focus of this paper by Henry Newrick.

Preamble

Many readers may have a sales or sales management perspective and could be reading this at any point in the wax and wane of a business cycle however, the marketing arguments convincingly postulated below seem equally applicable to prospecting and other sales lead generation activities, hence the inclusion of this powerful study by Henry Newrick:

Paper by Henry Newrick - Part 2 of 4

When you stop advertising here is what happens. Awareness and sales of your product or service will drop dramatically. This will be in direct proportion to the extent to which you cut back. An Arthur D. Little study of advertising budgets summed it up this way. “…If advertising support for an established product is withdrawn or substantially reduced and if there are no new economic or competitive developments of note, then sales of the product will decline exponentially”.

Many professional studies, controlled experiments and case studies underline the point. A classic study is that performed by research psychologist Dr H. Zielske and reported in the “American Journal of Marketing”. Dr Zielske found that advertising tends to be forgotten at a surprisingly rapid rate. Studying a 12-month advertising campaign with exposures once every four weeks, he observed a ‘saw tooth’ increase in awareness (i.e. after each exposure, a greater percentage of respondents could remember the advertising than at the previous exposure, but awareness invariably dipped sharply in between exposures).

He then did a second experiment which demonstrated even more dramatically the decline of awareness when advertising ceases. This study centred upon a 13-week advertising campaign, involving weekly exposures. Immediately after the campaign, 63% of respondents could remember the advertising but a month later, the percentage had decreased by half. Six weeks later, it had dropped by two-thirds. The implications for sales and profits are obvious.

In April 1964 the American magazine “Mediascope” reported on the findings of Dr J. Stewart who had been undertaking media research under the auspices of the Harvard Graduate School of Business. The test focused on the market introduction of two new products and their accompanying newspaper advertising.

Dr Stewart reported that:

- The advertising caused a rapid initial rise in awareness and sales – eight weekly insertions doubled the number of customers. Repeated advertising maintained awareness, but did not further increase it.

- When advertising was stopped awareness almost immediately began to fall – and business simultaneously began to fall too. Dr Stewart strongly advised advertisers to “give thought to viewing advertising programmes as capital investments rather than current expenditure.” Following are three examples from the United States showing what happens when advertising is reduced.

- A major cigarette brand was advertised on national television until July 1968. After that date, the ad budget was reduced and television was eliminated from the schedule. Advertising awareness (recall of having seen ads for the brand in the previous month) immediately began to decrease. In the first three months, it fell from a peak of 69% to 32%. Over the following year, it dropped still further to 24%.

- Another campaign was designed to create awareness of the availability of a new service on a nationwide basis. Over its 13-week duration, the advertising raised unaided awareness of the service from a benchmark level of 1% to 25%. Use of the service during this time rose to 6%. But when the advertising stopped, the use of the service dropped by more than a third in the first month alone.

- A household product was advertised on television from 1985 to 1989. During that time its advertising budget remained unchanged – but as media costs were constantly rising, the actual amount of advertising steadily decreased. Throughout that period, a corresponding decline in brand preference was observed. Then in April 1989, advertising was stopped altogether. Immediately the brand preference curve turned downward more steeply than ever – and continued to fall.

In regard to the above three examples, the conclusion is obvious. Brand awareness, brand preference and sales can be built quickly with proper advertising expenditure but will turn downward again when advertising stops or is reduced. The advertiser who withdraws his/her advertising spend in order to save money may in reality be sacrificing a major capital investment – an investment in brand awareness and brand preference – that could be very difficult and expensive to regain at a later stage.

More Research

In 1980 Fairchild Publications (a division of Capital Cities Media) publisher of Women’s Wear Daily published the following document.

Advertising in a Recession

As business executives look to cut overhead and become a “lean, mean machine” in this recession, it’s easy to view advertising as an expense that’s easily expandable. However, there have been a number of studies whose findings contradict this theory and come to the same conclusion: It pays to advertise in a recession.

A 1979 study by the research company ABP/Meldrum & Fewsmith examined the sales and net income of companies that cut advertising budgets during the 1974-75 recession and compared them to the sales and incomes of companies that did not cut.

A total of 173 companies were studied and their results were tracked from 1972 to 1977.

Companies that cut advertising budgets had minimal sales growth in 1974, suffered a decline in 1975, and increased sales by only 70% during the five-year period.

On the other hand, companies that did not cut their budgets suffered no slowdown during the recession and increased sales 150% over the five years. Net income showed a similar pattern.

The most significant finding was that the momentum gained by steady advertising during the recession helped companies grow at a faster rate in 1976 and 1977 once the recession had ended.

The conclusion from these studies is that increased brand awareness creates an improved potential for market share, which in turn creates a better potential for higher return on investment. The data demonstrated that most businesses succeeded in realising these potentials once the levels of brand awareness were achieved.

The start of the process is brand awareness – without it, both market share and ROI are severely jeopardised.

All available evidence indicates that advertising can be the BEST INVESTMENT a marketer can make during a recession. Advertising aggressively in a recession can not only boost sales and market share but can also open a company’s lead on its more timid competition. It can skilfully reposition a product to take advantage of new purchasing concerns, give the image of corporate stability within a chaotic business environment and give the advertiser a chance to dominate its chosen advertising media.

Another study worth considering is the work of American marketing consultant-economist Vernon Van Diver who in the 1960’s developed a way of predicting a company’s sales based on its share of the total advertising in its product category. Many case studies led him to this conclusion:

An increase or decrease in an advertiser’s share of marketing results in a corresponding increase or decrease in his share of the market.

And his belief that levels of sales are directly tied to levels of advertising was strikingly confirmed by his classic study of Westinghouse sales for 1962. That year, Westinghouse cut its advertising budget to $8.3 million from its 1961 figure of $9.5 million. The cut-back dropped its share of total advertising in its competitive field from 28% in 1961 to 22% in 1962. Westinghouse’s market share in 1962 dropped 10% from its 1961 level – a direct consequence of the reduction in advertising.

So sure was Van Diver of the cause and effect relationship between advertising levels and sales that he was prepared to estimate well ahead of time the 1962 sales results for Westinghouse, General Electric and Allis-Chalmers. He did this by relating each company’s advertising budget to its previous budgets since 1958, and to the total outlay for all three in 1962, thus arriving at what he called an ‘advertising trend’.

Believing that every dollar deviation up or down from the advertising trend has a certain ultimate value in determining final sales figures, Van Diver calculated that value for each of the three advertisers. He then related it to the amount by which each was over or under the trend line to arrive at his estimates of their 1962 sales figures.

The results were startling. Van Diver’s estimate for Westinghouse sales was $1.99 billion. The actual figure proved to be $1.954 billion, a difference of just 1.829%. His estimate of $4.79 billion for General Electric was an incredibly small 0.068% off the actual total of $4.792 billion. And for Allis- Chalmers, Van Diver estimated sales of $558 million, only 4.26% off target from the actual result of $516 million.

The whole exercise was a powerful endorsement of the principle that sales levels are heavily dependent upon advertising levels. And Van Diver was critical of companies that cut back on advertising because of changes in the economy. As he noted, “Advertising volume is up now, down later, according to the economic weather, according to last year’s sales or what these sales are expected to be”.

He says it is silly for a company to invest millions of dollars in a marketing programme they let be controlled by such erratic and diverse factors.”

These and many more case histories that could be quoted provide impressive evidence that advertising expenditures should never be cut, even in periods of economic downturn. But the question remains – why is it so?

Why does a well-established product immediately lose market share merely because its advertising frequency is reduced? Why doesn’t its popularity with consumers carry it through a period of communication cutback?

Compiled and edited by Henry Newrick Team House, 208 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN2 2DJ. United Kingdom. Tel. 0845 222 0053. http://www.henrynewrick.com/

Post-Amble

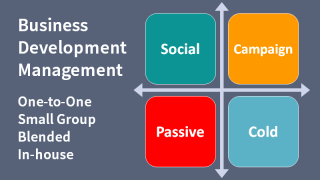

Strategy drives tactics. Business strategy informs the marketing strategy which in turn determines the marketing tactics that are combined to form a marketing plan. The overall plan must accommodate the business cycle and drive marketing investment. The tail wags the dog when short-term business fluctuations dictate marketing investment.

Clive Miller

Related Documents:

Selling in a Falling Market

8 Emergency Steps for Selling in Difficult Times

Develop Creative Thinking to Solve Sales Challenges

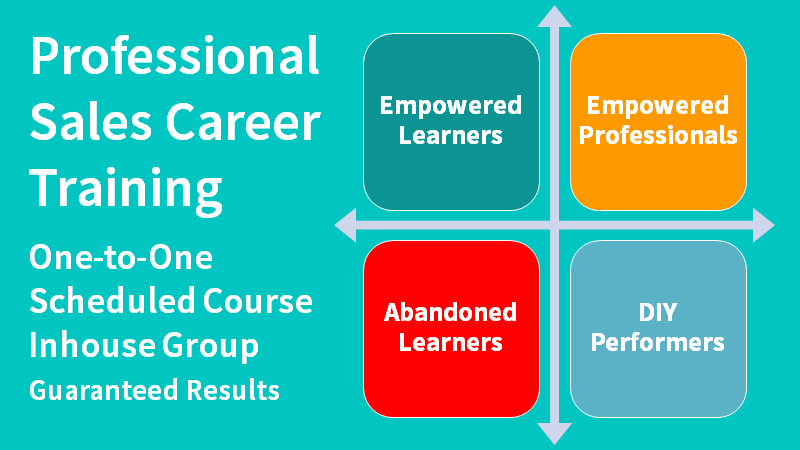

Business Survival Sales Training

If you need to create a winning marketing strategy or improve a marketing plan, we can help. Telephone +44 (0)1392 851500. We will be pleased to learn about your needs or discuss some options. Alternatively Send email to custserv@salessense.co.uk for a prompt reply or use the contact form here.